Independent Livestock Analyst, Simon Quilty of Global Agri Trends shares his thoughts on how Chinese demand for Australian meat might bounce back.

There has been much press and speculation about China’s economy slowing down dramatically due to the collapse in the property market, a dramatic fall in Chinese equities and rising unemployment of close to 25 per cent (pc) in their youth.

The concern is that China has shifted away from big stimulus packages of the past to more moderate measures, such as the recent interest rate cut, which points to a potential long-term period of slow economic growth that could last ten years.

With China being one of our major markets, what could be a negative for Australian lamb and beef producers may actually be a positive if history is any guide.

In the 1990s, Japan suffered a prolonged recession post the economic bubble of the 1980s, whereby economic stagnation and slow growth occurred for ten years – this period became known as the ‘Lost Decade’.

In this article, I will compare the two periods across China and Japan to the impact on meat consumption in Japan during the Lost Decade. It discusses whether a similar scenario will occur in China today. Interestingly, meat consumption rose significantly in Japan during the Lost Decade and imported meat prices increased substantially.

What on the surface would seem like a difficult period for meat consumption turned into a boom for Australian beef exporters, and there is a strong argument that China could do the same again.

How is China today similar to Japan’s economic woes in the early 1990s?

- China is starting to experience deflationary pressure, which Japan experienced for ten years back in the 1990s.

- A recent sharp decline in China’s July imports highlights how domestic demand is very sluggish, with companies in China reducing prices to try to attract buyers. This can be a vicious cycle, and consumers look to defer purchases. Similarly, in the 1990s, Japan’s aggregate demand fell after the collapse of the bubble economy.

- Japan had the so-called ‘three excesses’ in the 1990s; corporate debt, production capacity, and high unemployment. Attention was drawn to the nonperforming loan problem of financial institutions. It should be noted that in 1999, almost 22.5 pc of Japanese college graduates were unemployed. China today is suffering from the same three excesses.

- Japan's real estate prices peaked in 1991 and then fell, no different to recent times, with China’s real estate prices falling close to 25 pc since October 2021 in most major cities. By the end of the Lost Decade, Japan’s land values fell 70 pc by 2001. Ongoing falls in China’s real estate market is expected.

- Today, China also has three similar excesses with 25 pc or greater unemployment rates for young people. Corporate debt is at record levels, with corporations unsure about future economic growth and have entered a ‘wait and see’ mode. Lastly, China’s industrial production capacity has fallen in Q2 to 74.5 pc (from 75.1 pc a year ago), with mining and manufacturing both falling the most.

However, one of the critical differences is that Japan put up interest rates aggressively in late 1989, from 2.5 pc to 4.25 pc and then to 6 pc by mid-June 1990. In contrast, China's interest rates have been falling since 2012 from 6.5 pc, and today are at 3.55 pc.

Long-term slow growth in China seems inevitable

The problem of debt-laden municipalities is not going away, and policymakers within China need drastic changes to the economic framework of China to stop this from reoccurring. To keep throwing money at these problems, as they have done in the past, is not working, and it seems that both the Chinese government and people must accept that the four decades of growth at a blistering pace is unsustainable.

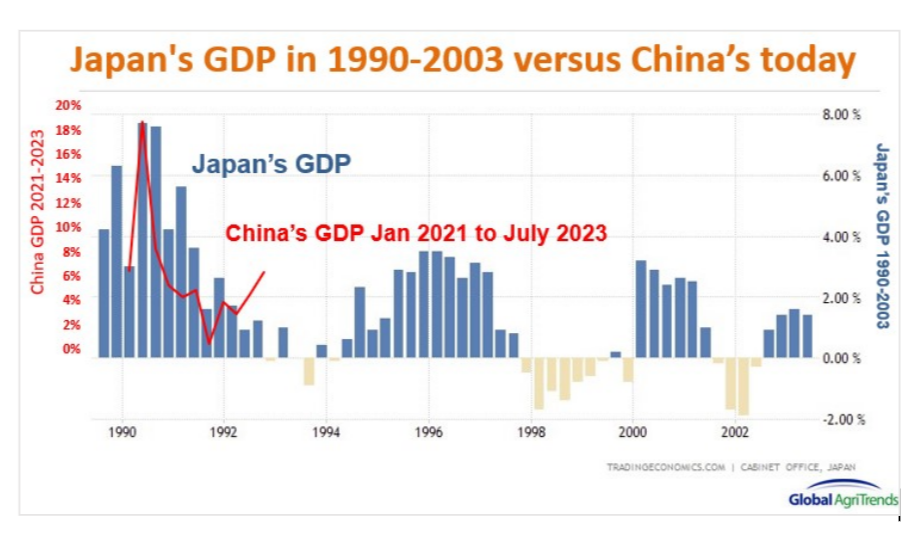

As we saw with Japan, who had ten years of low economic growth between 1991 to 2003 of only 1.14 pc annually, well below that of other industrialised nations at the time, China could see the same deficient economic growth.

When comparing Japan’s growth back then with China’s today, there is an uncanny resemblance, albeit at higher percentages for China. This would imply that if a decade of slow growth occurred, it would be closer to 2.25 pc for China, equivalent to the 1.14 pc for Japan in the ’90s.

When reflecting on the Australian dollar (AUD) and what it did back in the 90s when Japan went through this period of low growth, the AUD fell 19 pc from where we are today, equivalent to over ten years. It should be noted that China, at that point, was not the powerhouse it is today, with only 3.6 pc of Australia’s exports going there. In 2023, this figure is closer to 34 pc.

Japan’s impact on imported meat during the Lost Decade

Australia and the United States have been essential suppliers to Japan over many decades. The impact on Australia’s exports during the 90s might be an essential guide on where Australian exports may go with China if a similar low growth period should occur.

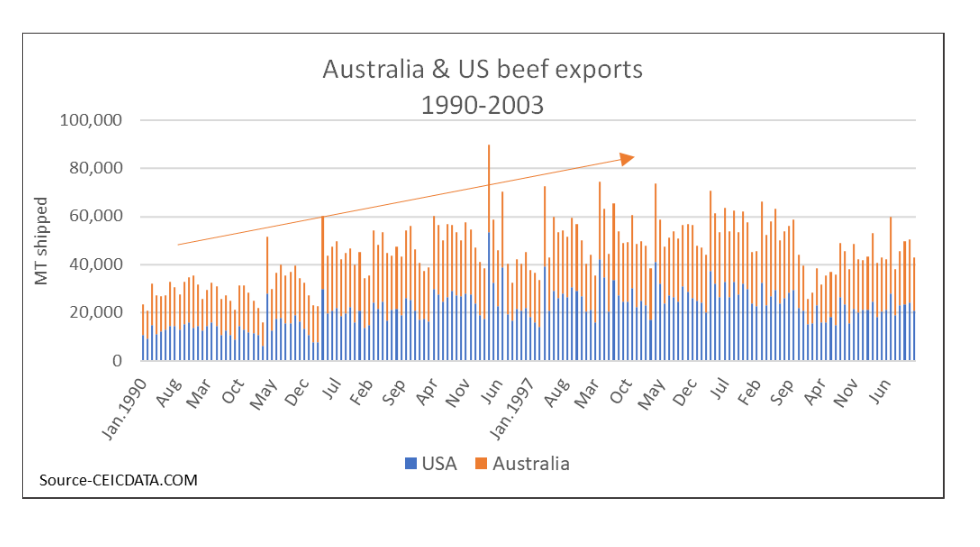

During a slow growth period, Australia’s exports to Japan saw exports from both Australia and the US increase dramatically over ten years from 1991 to 2002, with volumes doubling from 341,000 (both US and Australia imports) to 677,000 megatonne by 2000.

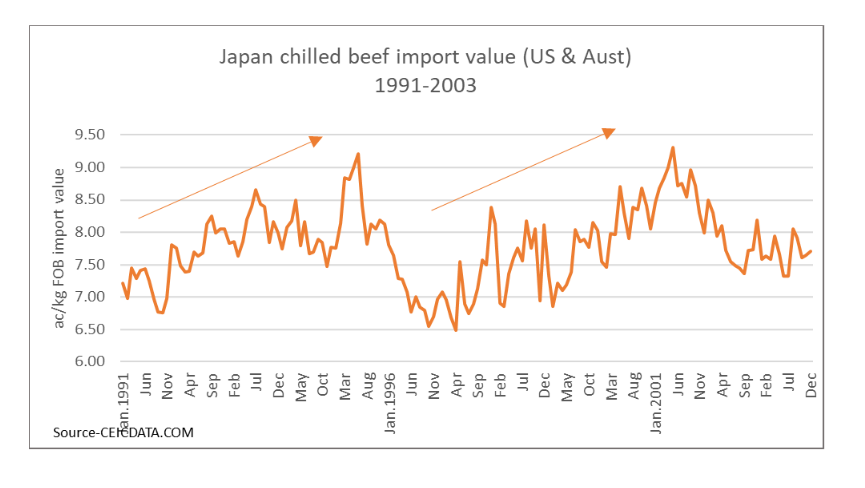

Beef import values into Japan strengthened over the first five years of the Lost Decade, increasing by 32 pc, and then a correction occurred in 1996-97 due to a recession. Then, a recovery saw 2001 prices rebound again by 40 pc. In other words, during these slow GDP growth years in Japan, beef imports grew by almost 100 pc, and prices finished 40 pc higher (in AUD terms) than at the start of the decade.

Chart shows the quantity of Australian and US beef exports between 1990 and 2003.

Chart shows the quantity of Australian and US beef exports between 1990 and 2003.

Chart shows Japan chilled beef import value between 1991 and 2003.

Chart shows Japan chilled beef import value between 1991 and 2003.

Why did Japan consume more imported beef during the 1990s?

Japan’s increase in beef imports can be related to several factors during the 1990s.

Firstly, the contraction of manufacturing within Japan during the 1990s saw what is called the boomerang effect, where many Japanese firms, directly or through subsidiaries, produced beef overseas for export to Japan, which saw Japan's beef imports increase.

This was very much the case in Australia’s meat processing and feedlot sector in the 1990s, with over one-third of meat processors having foreign ownership, of which half had Japanese ownership in Australia. In the feedlot sector, Japanese ownership was even greater with almost 50 pc of Australia’s feedlot capacity by the mid-1990s having Japanese investment of some sort. So, meat produced within Australia had a direct pipeline into Japan.

Secondly, in the backend of the Lost Decade (1990-2000), Japan’s cattle herd liquidated, and domestic beef production fell by 25 pc from 1995 to 2001. This saw Australian and US import volumes pick up to fill this void.

In the late 80s and 90s, beef demand in Japan surged, mainly on the back of yakiniku (beef barbecue) restaurants and an overall trend towards dietary westernisation.

Even with a slow growth rate in 1990, Japanese households devoted a larger share of their incomes to maintaining their level of consumer spending. Although they had experienced significant declines in share prices and house values, they had such large amounts of liquid savings in postal savings accounts and banks that they did not need to increase savings to rebuild assets. So, consumer spending continued, and savings gradually declined. By the decade's end, savings had halved from 10 pc of household income in 1990 to 5 pc by 2000.

In comparison, China’s household savings today is one of the highest in the world, rising from 16 pc of disposable income in the 1990s to over 30 pc. This gives plenty of scope for these funds to be rediverted in maintaining China’s standard of living, with ongoing beef and lamb consumption likely.

Finally, in 1995, the Japanese Government agreed to drop beef tariffs from 50 pc to 38.5 pc over four years. For the first time, cheaper beef became a viable export from Australia and the US to Japan due to reduced tariffs.

USDA report forecasts increased meat consumption in China

A recently released USDA report investigated the question: ‘Has China’s consumption of meat reached a ceiling, or is there room for more growth?’

The USDA study investigated trends in China’s meat supply and household purchases; it discussed data inconsistencies, analysed population, income, and price data that influence consumption, and estimated using statistical models to ascertain future growth in China’s meat consumption.

One of the key findings of the China consumption report was based on past relationships between meat consumption, income, and prices. China’s per capita annual meat consumption is projected to rise from 2022 to 2031 by 23 kilograms using consumer purchase data and 21 kilograms using disappearance data. Pork consumption is projected to grow slower than other meats (beef, mutton, and chicken). The report forecasts that the ten-year growth would occur as follows: 4 pc for pork, 5.8 pc for beef and mutton, and 2.4 pc for poultry.

To put this in perspective, China’s population in 2031 is expected to be 1.5 billion people, and an extra 5.8 per cent increase would equate to imported beef demand increasing to 3.2 million tonnes per annum, an additional 500,000 metric tons of imported beef would be required (assuming the domestic herd remains constant) over today's import beef needs.

In addition, the report concluded that pork consumption is relatively insensitive to income, but poultry, beef and mutton consumption is more responsive to income growth.

The findings were that China's pork share of the protein market has declined but still comprises more than half of consumer meat expenditures. Poultry consumption decreased during outbreaks of avian influenza when cases in humans occurred, whereas beef and mutton consumption continued rising despite significant price increases.

So, the expected growth in China’s beef consumption might not be the same reason that Japan’s growth occurred in the Lost Decade, but the endpoint is the same.

Conclusion

The similarities between Japan in the 1990s and China today are far greater than their differences, and if history repeats itself, it is possible there will be a long period of slow growth in China of approximately 2.25 pc per year growth.

The question arises of whether demand for imported beef and lamb would be maintained in China if a period of slow growth should occur. If Japan is any guide, the answer is yes, but this came about due to many factors.

There is not the same investment in Australia’s feedlot and meat processing sector today from China compared to Japan in the early 1990s so the boomerang effect will be minimal. There has not been the same contraction in China’s cattle herd (as far as we know) compared to Japan's 25 pc contraction in the back half of the 90s, so there is no apparent supply void. However, the desire for beef and its preference by middle-class China is still alive and well.

In conclusion, a slow-growth China market is a real possibility. A falling Australian dollar into the 40s (US cents) over ten years is a real possibility. China’s demand for beef and lamb may not be impacted by the slow growth. It is more likely to increase demand as consumer spending is maintained and their savings rediverted.

It’s potentially the best of both worlds for Australian lamb and beef producers: a low Australian dollar and strong demand for protein.